More "What's New"

This page is an archive of the entries that have previously appeared in the "What's New" section on the Home Page.

Alan Chadwick often alluded to a mysterious but powerful force that strongly affected the resulting productivity of the garden. "Attitude of Approach" was the term he used to refer to this essential quality of the gardener which, if correctly aligned, could bring out a magic luster and heightened productivity. Richard Joos here gives an articulate expression of this subtle but all-important aspect of Alan Chadwick's philosophy.

"Alan Chadwick, a gardener of pure genius," were the words that the Countess Freya von Moltke used to describe her friend who, she said, would be perfect for the job of leading the newly envisioned garden project at the University of California at Santa Cruz. The garden that Alan created there became, according to poet Donald Nicholl, "the most famous four acres in California." Nicholl's 1966 lecture on "A Sense of Place" proved to be the catalyst that inspired the early visionaries, Paul Lee, Freya von Moltke, Page Smith, Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy, and of course, Alan Chadwick, to focus their spiritual energies on the realization of a garden that would reconnect human beings to what was truly meaningful in the world.

After the Death of Suzuki Roshi in December of 1971, Richard Baker assumed the leadership of the San Francisco Zen Center. Immediately after that transition, Zen Center made the decision to purchase an 85 acre former cattle ranch in Marin County called Green Gulch Farm. Having previously met Alan Chadwick back in 1967, Baker decided to invite Alan to direct the agricultural efforts there. This was a risky move in more ways than one. First, Zen members were wary of outsiders being involved in the new project. Second, Chadwick's temperament was not the soft-spoken, gentle manner of the beloved teacher, Suzuki Roshi. Would it all work out? Here we present answers to that question from the point of view of several Zen Students who participated in this grand experiment.

In August of 2012, Skip Kimura told us, "Some of Alan’s students who went on to work in biodynamics — I don’t know how they feel now — but at the time they felt like they needed to repudiate Alan in order to be real biodynamic people, which I sort of thought was silly."

Silly or not, Skip is right, there has been a schism between Alan Chadwick followers and adherents of anthroposophical biodynamics for years. Andrew Lorand, PhD here addresses this problem and offers a cogent argument as to why such an attitude is unnecessary.

Yet another example of unreliable scholarship presented by the University of California at Santa Cruz as Oral "History." One has to wonder why UCSC has published so many accounts of Alan Chadwick by individuals who distort the truth in order to cast him in an unfavorable light. Is this pattern intentional? If so, what possibly could be the motive for such a campaign of misinformation?

There is no denying that Alan Chadwick could get irascible from time to time, but it was not so difficult to avoid being on the receiving end of his tirades. Here we offer a few tried and true tricks that were generally effective in avoiding his sometimes rambunctious ill humor. Managing Alan's Temper was an essential skill that his apprentices learned along with the horticulture, and such psychological insights were valuable lessons that would come in handy in later life.

During those early happy days at Santa Cruz, before all the political intrigues fomented by back-biting usurpers brought them to an end, Alan Chadwick would often tell stories of his youth and apprenticeship days in England. On one such occasion, Alan described an audacious act of sabotage against a factory farm that was treating animals in an unacceptably cruel manner. Although this occurred in his youth, Alan never lost his abiding sense of duty and protection toward the animal world. In these Stories from the Glasshouse, we also hear about how Alan instructed an apprentice to prevent the deaths of honey bees that found their way into the greenhouse in the spring of 1971.

The Clairevoyer - Corbin & Chadwick: Draft notes on some interesting parallels between the work of Henry Corbin and Alan Chadwick, with reference to horticultural devices in Renaissance madonnas.

― By Rodney Blackhirst, PhD

In addition to his horticultural teachings, Alan Chadwick employed a whole arsenal of techniques to prod his apprentices onward toward greater levels of personal mastery and self awareness. It is for that reason that we have chosen the descriptive phrase Gardener of Souls to summarize his effects on the personal development of his students. Not everyone knew how to benefit from the particularly demanding style of teaching that he used, but for those who did, it generally was a transformative experience. We here attempt to describe briefly the main lines of Alan's pedagogical approach so that those who were not consciously aware of his methods at the time can retrospectively understand why he behaved the way he did.

Part of the apprentice training at Covelo included reading some of the classic texts of organic gardening and farming methods. Skip Kimura pointed this out in an interview he did with us in the summer of 2012. One of the authors he mentions there is Sir Albert Howard, the first to develop modern composting methods that can convert waste materials into life-giving humus for the soil. Here we present an excerpt from, "An Agricultural Testament" by Sir Albert Howard, which describes Nature's Methods of Soil Management. This is an inspirational introduction to soil management based on natural processes that were very close to the methods employed by Alan Chadwick.

Alan Chadwick could inspire antipathy and fear in certain types of people even though he had done nothing threatening, harsh or impolite. Some individuals simply found him personally intimidating, and so responded inwardly with fear and judgmental antipathy. Here we explore this phenomenon in greater detail using, as an example, an oral history interview conducted by the University of California at Santa Cruz in 2008.

While few people would dispute that Alan Chadwick had a profoundly positive influence on sustainable agricultural practices during the 20th century, not everyone is equally sanguine about his personality. Some have even criticized him for his irascibility and tempestuous nature. How did Alan come to embody such diverse character traits within the complex unity of his psychic life? We here present one former apprentice's view on this intriguing mystery.

When marauding skunks threaten the young chicks being raised for future egg production at The San Francisco Zen Center's Green Gulch Farm, Alan Chadwick determines that they must be trapped and subsequently relocated to where they can do no harm. He then instructs one of his trusty apprentices in the high art of skunk trapping. Here, for the first time ever, Alan's secret method for catching those stinky critters without getting sprayed is revealed for all the world. Remember: ―You saw it first at Alan-Chadwick.org.

Our collection of inspiring quotes about gardening, nature, and life has been greatly expanded. Some pithy examples:

"Gardening is civil and social, but it wants the vigor and freedom of the forest and the outlaw." ― Henry David Thoreau

"One should respect public opinion insofar as is necessary to avoid starvation and keep out of prison, but anything that goes beyond this is voluntary submission to an unnecessary tyranny." ― Bertrand Russell

"Everything I did in my life that was worthwhile I caught hell for." ― Earl Warren

Allen Kalpin describes some of the anguish involved in the transition from the Garden Project at the University of California at Santa Cruz to its continuation at the San Francisco Zen Center's Green Gulch Farm. What was to have become a great collaboration and cross-fertilization between the horticultural mastery of Europe and the contemplative depths of Asian Zen Buddhism turned into a stormy clash of cultures where unfulfilled expectations and horrible weather conspired to undermine the heroic intentions of all involved. Allen here describes the initial period working at the Zen Center with Alan Chadwick after The Move to Green Gulch in the Spring of 1972.

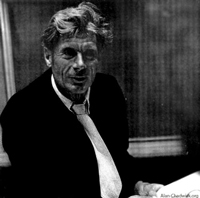

A photograph of Alan taken in 1971 while he was delivering a lecture at the University of California at Santa Cruz. This is one of our absolute favorite pictures of Alan, as it truly captures the theatrical flair that invariably accompanied his every utterance. He always strove to elevate an idea to the point at which it would leave a lasting impression on his listeners. There have been other gardeners as good as Alan was, but there have hardly ever been gardeners as good as Alan who were also superb communicators. This was his particular genius.

As we have described elsewhere on this site, Alan Chadwick was an accomplished Shakespearean actor. But after dedicating himself to educational garden projects, as encouraged by the trusted advice of his revered friend, the Countess Freya von Moltke, Alan still managed to find fresh outlets for his irrepressible theatrical nature. Life in general became his stage, and he seized on every opportunity to make the day-to-day ordinary world sizzle with the electricity o f the dramatic. Like an imperious maestro, he transformed every minor decision into an earth-shaking crisis, every unfamiliar concept into a profound secret of ancient mystery wisdom, every temporary lapse by an unsuspecting apprentice into a capital offense. He had a mischievous side as well, and, like Puck in Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream, Alan made sure that you were always on your toes, never knowing what to expect next. On other occasions, he would channel his dramatic talents into his various talks, lessons and lectures, enlivening them with wonderfully engaging fairy tales in order to underscore the moral message of his fables. Here we present transcriptions of three of those Fairy Tales, delivered a few short months before his death at Green Gulch.

f the dramatic. Like an imperious maestro, he transformed every minor decision into an earth-shaking crisis, every unfamiliar concept into a profound secret of ancient mystery wisdom, every temporary lapse by an unsuspecting apprentice into a capital offense. He had a mischievous side as well, and, like Puck in Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream, Alan made sure that you were always on your toes, never knowing what to expect next. On other occasions, he would channel his dramatic talents into his various talks, lessons and lectures, enlivening them with wonderfully engaging fairy tales in order to underscore the moral message of his fables. Here we present transcriptions of three of those Fairy Tales, delivered a few short months before his death at Green Gulch.

Very few of Chadwick's California apprentices knew Alan during the time that he worked in Virginia, the last garden project that he made before he died. That period of his life remains something of a mystery to most of us. One person who worked with Alan there, Craig Siska, was interviewed recently by the folks at Biodynamics Now!. In this audio recording he describes something of what life was like back then, and how he interacted with Alan at the time. The photo at right shows Alan working in the gardens near New Market, in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia.

Alan Chadwick had a distinguished Career in the Theater before turning his attentions exclusively to horticulture. The theater was the one great love ofhis life, and in fact, he sacrificed his inheritance for it. At the tender age of twenty-one, Alan informed his father, the Duke of Pudlestone, that he had decided on a career in thetheater. His father, eighty-four years-old at the time, calmly replied that the theater was no place for a gentleman, and that if Alan insisted along those lines, then he would simply be disowned. Alan thought very seriously on the question for a week or so, then firmly made up his mind. He loaded his Irish Wolfhound into his Rolls-Royce, drove to London, and never looked back. We here present a collection of photographs and reviews from Alan's performances during the time that he acted with the National Theatre Company in South Africa. Some apprentices even remember seeing Alan performing in productions of Shakespeare at the University of California in Santa Cruz during the early days.

Because so many resources about Alan Chadwick are available on the internet, we here at Alan-Chadwick.org work tirelessly to keep our readers up to date on those materials (see here, for example). We also do our best to help readers decide which of those resources are reliable, and which are laden with errors, personal biases, or historical revisionism. Even after the lapse of forty years, some people persist in their attempts to impugn Alan's legacy as a justification for their own roles in the dirty politics of the day. As a case in point, we here offer two strongly contrasting points of view on "A Golden Time in the Garden" at Santa Cruz, where Alan made the first, and possibly the finest, of his teaching gardens in the United States.

Dan McGuire talks about his impression of the garden that Alan Chadwick made at the University of California at Santa Cruz, and about the mission that inspired Alan in this effort. Originally written as a prelude to a book of Alan's lectures, Dan's articulate comments stand on their own as an expression of his individual experience, which was also the experience of many others who wandered into the paradise on that hillside. Dan's position as student president of the Garden Project gave him a unique perspective on Alan's attitude of approach to life and to gardening.

Maria von Brincken was a student in one of. Paul Lee's classes at the University of California at Santa Cruz when she first heard about the Student Garden Project. It did not take long for her to decide to become one of Alan's apprentices. She entered quickly into the rigorous regime of the garden activities which began at dawn every morning while at the same time keeping up with her academic classes. Maria shares some of her memories, along with a photo of Alan where she is in the background. This photograph of Alan is a classic, as it captures him in a very characteristic pose.

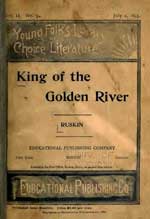

The original version of a story that Alan Chadwick often told in his own words was John Ruskin's classic, The King of the Golden River. Here we present Ruskin's original 1895 text of the fable that resonated so strongly with Alan. Generosity and charity triumph over greed and egotism with nature providing the final judgment, just as Alan would have it. Forgiveness has a place in the overall scheme of things too. The younger brother, Gluck, mourns the loss of his older brothers despite their long history of abuse toward him. Although Alan could hold a grudge for a long time, he could also forgive. One time a generous philosophical mood came over him in the early days at Covelo. It was at the end of a hard day's work, and Alan and a few of his close apprentices were sharing a glass of wine as twilight gradually gave way to a night scintillating with stars. Somehow the subject of forgiveness came up, and Alan declared that he had pretty much forgiven all those who had done him wrong in his life, even those, he said, who had betrayed him in Santa Cruz. Perhaps someday we can persuade the former apprentice, who heard Alan say this, to relate more of the details of that conversation.

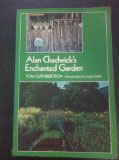

At long last, we add a book review of "Alan Chadwick's Enchanted Garden," by Tom Cuthbertson to our collection of reviews of published sources dealing with Alan's life and work. The introduction was written by Page Smith, a long-time friend and ally of Alan's at the University of California at Santa Cruz. This book describes many of the garden techniques used in the Chadwick Garden in Covelo, California, during the late 1970's.

A newly published collection of Alan Chadwick's lectures have been released by Steve Crimi, who transcribed and edited these talks. They are taken from the period of 1975 to 1980, with the last one delivered only weeks before Alan's death at Green Gulch. The book is titled, Reverence, Obedience and the Invisible in the Garden, and is meant to be a sequel to Performance in the Garden, reviewed below. The book's foreword claims that this latest collection of lectures represents a deepening of the themes addressed in the earlier collection, and the reader is not disappointed. Profound, eloquent, and evocative of the genius that was Alan Chadwick.

Additional photographs of the Saratoga Community Garden from the personal archives of Betty Peck, who was the founder and organizer of that project. This collection also includes a number of high-quality black and white photos by Dwight Caswell. The image-detail at right, for example, shows Anna Peck (later Rainville) as she leads an enthusiastic group of children in various garden activities. Anna's first exposure to Biodynamic farming was through her friendship with Alan Chadwick there at the Saratoga Community Garden, and through the lectures that Alan gave at the Villa Montalvo Center for the Arts in Saratoga. Other photos in the collection show Adrienne Borg, Sue Bolton, and Lee Anne Welch, all early and important collaborators in that project. Many thanks to Dwight Caswell and Betty Peck for permission to reproduce these rare images.

Greg Haynes relates the time that Alan Chadwick consulted dowsers to find the best location for a well that the University administrators had agreed we could drill on the new farm site at UCSC. Not all went according to plan, however, as certain types of limestone can confuse the signals that dowsers use to identify underground water.

We have just been notified that a new edition of Paul Lee's book on Alan Chadwick is now available and can be ordered from Amazon.com. The title is: There is a Garden in the Mind: Alan Chadwick and the Origins of the Organic Movement in California. This is a must-read for anyone who wants to understand Alan Chadwick's place in western philosophical currents going back many hundreds of year

After Alan Chadwick's involvement at the Green Gulch project came to an end in 1973, he lived for a time in Saratoga while h e casted about for a new venue to continue his mission to redeem the lost youth of America and spread the knowledge of organic gardening. It was then that Richard Wilson offered him a piece of land in Covelo and invited him to begin work there. Richard's account of Alan's involvement at Covelo is highly readable and offers an insightful perspective on the man, Alan Chadwick, including both his strengths and weaknesses. Richard was interviewed by the Regional Oral History Office of the Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley in September 2001. The parts of his story that pertain to Alan Chadwick are reproduced here. We also provide a link to the entire set of interviews that describe in detail Richard Wilson's work as a conservationist in California over many years. This publication is of great interest to all of us for whom Richard has always been something of a mystery.

e casted about for a new venue to continue his mission to redeem the lost youth of America and spread the knowledge of organic gardening. It was then that Richard Wilson offered him a piece of land in Covelo and invited him to begin work there. Richard's account of Alan's involvement at Covelo is highly readable and offers an insightful perspective on the man, Alan Chadwick, including both his strengths and weaknesses. Richard was interviewed by the Regional Oral History Office of the Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley in September 2001. The parts of his story that pertain to Alan Chadwick are reproduced here. We also provide a link to the entire set of interviews that describe in detail Richard Wilson's work as a conservationist in California over many years. This publication is of great interest to all of us for whom Richard has always been something of a mystery.

Jackie Welch relates an amusing anecdote about Alan's reply to a question from the audience after one of his lectures in Saratoga. Alan was never at a loss for something to say, even if he did not have a direct solution to a problem. Priceless.

The four lectures that Alan Chadwick delivered at the Villa Montalvo Center for the Arts in Saratoga(1972) are now posted on this website for listening over the internet. This is one of the most comprehensive and straightforward of Alan's lecture cycles because it includes most of the themes that he regularly touched on in his talks. Some people consider these lectures to be his best presentations ever.

Michael Stusser describes his experiences working with Alan Chadwick at the very beginning of the Garden Project in Santa Cruz and how the Countess Freya von Moltke played an important role in bringing Alan to the  university. He tells a bit about the process of making his documentary film, Garden (1971), despite Alan's resistance to the idea. Alan did not like cameras, Michael says, and would throw dirt clods at him if he tried to capture Alan on film. Consequently, the film focuses mostly on the garden itself, and the students working in it. Fortunately, Michael did manage to slip-in a short clip of Alan for posterity. After working in Santa Cruz, Michael spent five years in Boulder Creek helping Jim and Beth Nelson to set up the gardens at Camp Joy. Michael was then recruited to be the garden teacher at the Farallons Institute in Occidental, California, now known as The Occidental Arts and Ecology Center. He currently owns Osmosis Enzyme Baths where he has set up an extensive Japanese-style meditation garden.

university. He tells a bit about the process of making his documentary film, Garden (1971), despite Alan's resistance to the idea. Alan did not like cameras, Michael says, and would throw dirt clods at him if he tried to capture Alan on film. Consequently, the film focuses mostly on the garden itself, and the students working in it. Fortunately, Michael did manage to slip-in a short clip of Alan for posterity. After working in Santa Cruz, Michael spent five years in Boulder Creek helping Jim and Beth Nelson to set up the gardens at Camp Joy. Michael was then recruited to be the garden teacher at the Farallons Institute in Occidental, California, now known as The Occidental Arts and Ecology Center. He currently owns Osmosis Enzyme Baths where he has set up an extensive Japanese-style meditation garden.

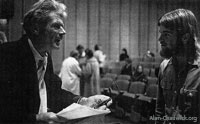

The photograph in the header of this page shows Alan Chadwick and Joseline Stauffacher in Santa Cruz. This is one of the many fascinating photos reproduced in Paul Lee's book on Alan (see above). Many thanks to Paul for permission to use it here on Alan-Chadwick.org. We also wish to thank Steve Sweet and Mary Beth Crawford for assisting with our most recent web page design upgrade.

In addition to the Bancroft Library transcripts and video, described above, Richard Wilson met with Peter Jorris and Greg Haynes on August 9, 2012 at Buck Mountain, Richard's home outside Covelo. In this video interview, he describes meeting Alan, inviting him to consider making a garden project in Round Valley, working with him over a period of five years, and Alan's subsequent departure from Covelo. Richard also tells of visiting Alan in Virginia when Alan was quite ill, and then arranging for him to return back to Green Gulch Farm in northern California where he eventually died.

Jackie Welch was a staff reporter with the Los Gatos Times Observer who wrote a series of articles on the progress of the Saratoga Community Garden from its conception in the mind of Betty Peck throughout all of its various stages of development. The community of Saratoga had originally hoped to secure Alan Chadwick as director of the garden project there, but Alan was committed to slug it out at Green Gulch, if possible, and so he sent one of his apprentices down to Saratoga to get that project going. Eventually he did relocate to Saratoga and participated in the garden there for a time, but this was merely a brief interlude before he eventually moved on to begin the project in Covelo. The articles that Jackie Welch wrote during the period 1972-1973 are presented here.

As part of the effort to recruit supporting members for the Round Valley Institute for Man and Nature, the fund raising arm of the Covelo Garden Project, The Garden Journal was published from time to time during those years. It was a very ambitious literary undertaking and the results were impressive. This little publication does succeed in capturing something of the flavor of the garden experience, mostly from the point of view of a Chadwick apprentice. This issue, Number 2, focuses on bees, clamping, fertilizations, legumes, festivals, and includes selections from the Covelo garden logs. Very handsomely illustrated. Reprinted here courtesy of Richard Wilson.

The first of the Covelo Garden Journals was titled:The Dirtman Journal, referring to the origin of the name, Adam, the earth's first gardener. It includes a lecture by Alan Chadwick on the subject of cultivation, an article on the herb, parsley, notes from the Covelo garden log, and more. Again, beautifully illustrated. A true work of art. It was prepared during the early months of 1976 by a cadre of garden apprentices and printed at the Yolla Bolly Press.

An illustration from the Dirtman Journal

The original Garden Project site at UC Santa Cruz, on the hill above the east entrance, is still maintained as a neat and pleasant horticultural area, now aptly named the Alan Chadwick Garden. In July of 2012 we paid a visit there to see what the place looks like today. We offer here a collection of photographs and observations from that day in Santa Cruz.

After Alan Chadwick was forced out of the University, the main focus of activity there at UCSC became the new Farm Project that Alan had initiated in 1971. He had laid out plans for the development of this much larger site, and had tasked us apprentices with fencing-in the area to keep out the grazing cattle. We also began construction on a "Roman Road" that was to be an artistic entry into the farm center, designed for foot traffic rather than for "exploding boxes," as Alan called the automobile. As it turned out, political intrigues intervened, and the farm project evolved along quite different lines than what Alan had envisioned. Here we present a series of photographs that depict the Agroecology Farm Program as it is today.

A photographic gallery of the present day town of Covelo, California, the site of Alan Chadwick's garden project from 1973 to 1978. Peter Jorris and Greg Haynes traveled there in August of 2012 and recorded a few of the sights so that visitors to Alan-Chadwick.org could form an idea of how the town looks now, almost 40 years later.

Photos taken in the late 1970's, by Richard Wilson, of Alan Chadwick's Garden Project at Covelo. Includes one interesting aerial photograph that shows the garden's layout very clearly. This was actually the second site that Alan cultivated in Covelo, as the first one had flooded in the torrential rainstorms of the winter of 1973-1974. This was perhaps just as well, as the first garden was plagued by convolvulus, commonly called bind weed or morning glory. We had to dig it out by hand, often following the roots down three feet or more. Photos used by permission, courtesy of Richard Wilson.

On August 22, 1974, Governor Ronald Reagan visits Covelo and meets with Richard Wilson and Alan Chadwick. Reagan is impressed with the garden and with the horticultural apprentices that he meets there, commenting that they are much better behaved than the anti-war protesters at Berkeley. Fortunately, Alan is on his best behavior as well, so Reagan did not have to experience his wrath. Several fascinating photographs from the private collection of Richard Wilson, and a brief description of the day. Photos published by permission, courtesy of Richard Wilson.

Stephen Decater talks about his experiences and reflections on working with Alan Chadwick, first in Santa Cruz and then in Covelo. Nobody worked closer and longer with Alan than Steve, so his perspectives are invaluable for gaining a sense of Alan's true character and the unique intensity by which he lived his life. It would probably also be fair to say that nobody has carried on the work that Alan began in North America so faithfully as Stephen and his wife, Gloria, herself also a Chadwick apprentice. For thirty-five years they have operated Live Power Community Farm in Covelo, one of the first Community Supported Agriculture farms in America, and a place where numerous apprentices and multitudes of school children discover the affinity between their own hearts and the spirit of nature.

One of the last apprentices at the Covelo project in 1977, before Alan left for Virginia the following year, was Skip Kimura. Skip subsequently went on to work in garden projects in Bolinas, California, and then in Michigan at the Waldorf Institute. Later, he was invited by Richard Baker, the abbot of the San Francisco Zen Center, to redesign and rebuild the gardens at Green Gulch. The original Chadwick garden there had been destroyed by several building projects, and the goal was to create a showplace in the style that Alan had pioneered a decade earlier. In August, 2012, Skip met with Peter Jorris and Greg Haynes in San Rafael to discuss his reflections about Alan Chadwick and his legacy in the world.

News articles about the Saratoga Community Garden from the years 1974 to 1981, mostly authored by Jackie Welch, staff writer for the Los Gatos Times Observer. This is the second part of these articles that chronicle the conception of the garden in Saratoga until its end when the land owners decided to develop the property that the garden occupied. This series includes many interesting quotes from Alan Chadwick and a few photographs of him when he paid an occasional visit to Saratoga. Thanks to Jackie for permission to post these photographs and articles here.

Photographs from the Saratoga Community Garden taken from the personal collection of Jackie Welch. These include a photo of Alan Chadwick taken when he attended an event there at Saratoga. Thanks to Jackie's daughter, Lee Anne, for her help with the publication of these items, including the newspaper articles described above.